Game theory and morality

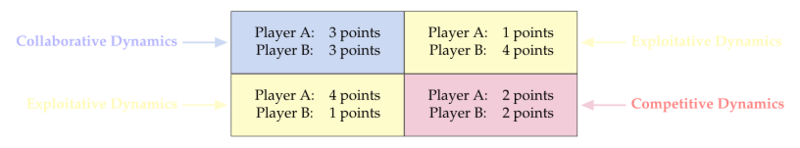

The prisoner's dilemma is an extensively studied scenario in game theory that shows why two rational individuals might not cooperate, even if it is in their best interests to do so. This happens because people cannot necessarily trust each other. In this introductory example, two players either have the choice to compete or cooperate. If both cooperate, they get 3 points each, while they only get 2 points each if both compete. However, if only one of them competes while the other cooperates, the competitor has a chance to get 4 points while the person that cooperates only gets 1 point. So if you don't trust the other player, the safest strategy is to always compete. When both players choose to compete, we can think of it as competitive dynamics, while when both decide to cooperate, we can think of it as cooperative dynamics. When one player chooses to cooperate while the other chooses to compete, we can think of it as exploitative dynamics.

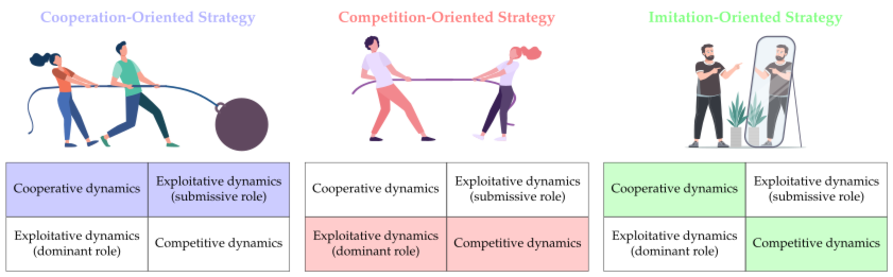

In the context of the prisoner's dilemma, players can adopt one of three fundamental strategies that orient their decision-making. The first is a cooperation-oriented strategy, where the player is inclined to cooperate with the other, irrespective of the other player’s actions. This approach can foster cooperative dynamics, yielding mutual benefits, or it may result in exploitative dynamics if one player assumes a submissive role and is taken advantage of by the other. The second is a competition-oriented strategy, which leads a player to consistently engage in competition against the other player, regardless of the other's stance. Such a strategy might create competitive dynamics with both players striving to surpass each other, or it could spawn exploitative dynamics where one player dominates, leaving the other at a disadvantage. The third strategy is imitation-oriented, where the player mirrors the other player’s actions. This approach can give rise to cooperative dynamics if the other player opts for cooperation, as the imitator will reciprocate with cooperation. Conversely, if the other player is competition-minded, the imitator will respond with competition, steering the dynamics towards a competitive nature.

The payoff matrix in the prisoner's dilemma is often misunderstood as being designed solely to promote cooperation. It may raise questions as to why the rewards for competing don't match those for collaborating. Some argue that competition should yield higher rewards because it drives innovation and productivity. Yet, competition doesn't exclusively reward the creation or innovation; it also rewards, and sometimes more effectively, strategies that undermine others. For instance, if unethical actions like polluting a river reduce costs and increase profits, competitive dynamics may inadvertently encourage such behavior. This is because individuals and entities operate under the belief that not engaging in such actions may put them at a disadvantage compared to those who do. The notion of "playing dirty" becomes a survival tactic in the race to stay ahead. Similarly, arms races epitomize competitive dynamics; nations arm themselves not just for gain but often out of fear of falling behind others. This dynamic shows that unchecked competition can lead to suboptimal outcomes for all, contrary to the collaborative gains envisaged in cooperative dynamics where the collective benefit naturally aligns with individual success.

In a world shaped by competitive dynamics, nations and corporations often find themselves trapped in a Nash equilibrium—a state where no player can benefit from changing their strategy while the other players keep theirs unchanged. This game-theoretic concept is vividly illustrated by military spending. Nations, out of a need to defend against potential threats, enter an arms race, perpetually escalating their military budgets in response to each other. Although intuitively, this seems like a safeguard, it paradoxically maintains a high-threat environment. If all could mutually agree to reduce military expenditures, the threat level would proportionally diminish. Yet, the fear of being outpaced militarily prevents any unilateral change, locking all players into a cycle of excessive spending that benefits none optimally.

Opportunistic cooperation refers to situations where, in the midst of competition, parties find short-term mutual benefits in cooperating. This can be exemplified by various types of agreements such as business contracts, military alliances, and other forms of cooperation. The idea is that "an enemy of my enemy is my friend" can lead to temporary cooperation even between rivals. One might argue that we should try to negotiate with China and Russia to spend less on our militaries, since that would benefit all of us. However, opportunistic cooperation is highly unreliable since when corporations or countries don't see a strategic advantage of collaboration, they tend to stab each other in the back. When corporations or countries don't see a strategic advantage of collaboration, they tend to prioritize their own interests over cooperation, and this can lead to a lack of trust between the parties. Without trust, cooperation can quickly break down, and parties may be more likely to act in ways that are detrimental to the other parties. This is where the phrase "to stab each other in the back" comes from, as it implies that one party will take advantage of the cooperation to gain an upper hand, and then end the cooperation for their own benefit.

Furthermore, the uncertainty of the outcome of cooperation and the potential for betrayal makes it hard for countries or corporations to make long-term investments in cooperation. This, in turn, makes it difficult to establish stable and mutually beneficial cooperation. Additionally, opportunistic cooperation can also be affected by external factors such as political or economic instability, which can also hinder cooperation efforts, as the parties might be uncertain of the future and would prioritize their own interests.

There are several historical examples of where opportunistic cooperation has later turned into an opportunity for one of the parties to defect. Here are a few examples:

- The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in 1939, which was an opportunistic cooperation between the two nations. The pact was an agreement of non-aggression, but it allowed the Soviet Union to gain territory and Nazi Germany to invade Poland without Soviet interference. However, Nazi Germany later violated the pact and invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, which marked the beginning of the Eastern Front in World War II.

- The alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union during World War II, which was an opportunistic cooperation between the two nations. The alliance was formed to defeat Nazi Germany, but it was an uneasy one, as the United States and the Soviet Union had different ideologies and goals. After the war, the two nations became rivals and engaged in a Cold War, which lasted for several decades.

- The alliance between the United States and the Taliban in Afghanistan in the late 1990s, which was an opportunistic cooperation between the two parties. The United States provided support to the Taliban in their fight against the Soviet Union-backed government in Afghanistan. However, after the fall of the Soviet-backed government, the United States turned against the Taliban, and the Taliban turned against the United States and its allies, leading to the current conflict in Afghanistan.

- The alliance between the United States and the Iraqi Kurdish militias during the Gulf War in 1991, which was an opportunistic cooperation between the two parties. The United States provided support to the Kurdish militias in their fight against the Iraqi government. However, after the war, the United States abandoned the Kurdish militias, and the Iraqi government turned against the Kurds, leading to a brutal repression of the Kurdish population.

These examples show that opportunistic cooperation can be useful in the short term, but it is often based on self-interest and the lack of trust between the parties. It can easily break down when the conditions change, and one of the parties might defect and pursue their own interest.

The phenomenon of cooperation, driven by mutual caring and emotional contagion, can be considered the domain of cooperative dynamics. This occurs when individuals engage in collective efforts, such as building a house, farming, or cleaning the neighborhood, without seeking personal gain from their co-participants. As social beings, we may derive inherent satisfaction from working together with others. In contrast, when individuals are driven by external factors, such as financial incentives or material rewards, their experience of satisfaction and overall well-being is often diminished in comparison to when they are motivated by intrinsic desires and personal motivations. This phenomenon has been extensively studied in the field of psychology and has been shown to have a significant impact on a person's satisfaction and happiness. Studies have indicated that individuals who are driven by extrinsic rewards tend to approach tasks with a more mechanical, transactional mindset and lack the passion and engagement that comes from being intrinsically motivated. They may also be less likely to invest their full effort, creativity and innovative thinking in a task, as their focus is centered on achieving the reward, rather than the task itself. On the other hand, when individuals are driven by intrinsic motivations, such as a sense of purpose, personal interest, or enjoyment in the task, they are more likely to approach the task with a greater sense of engagement and enthusiasm. They may also exhibit greater creativity and innovative thinking as they are more invested in the task for its own sake, rather than for external rewards.

It is worth noting, however, that competition can also stem from intrinsic motivations. However, this isn't necessarily harmful if we have playful competition embedded in cooperative dynamics. Playful competition seems like the only type of competition we should engage in if we want to survive as a species. Playful competition refers to a type of competition that is engaged in for fun and enjoyment, rather than for the purpose of winning or achieving a specific goal. It is a form of competition that is not taken too seriously, and it is characterized by mutual respect, fairness, and a sense of camaraderie. Examples of playful competition can include playing tug of war with a dog, playing football with friends, or engaging in friendly competitions in sports, games, or other activities. These activities allow individuals to engage in competitive behavior in a safe and controlled environment, and they can provide a sense of accomplishment and fulfillment.Playful competition is considered as an essential aspect of human development as it allows individuals to develop important social skills, such as teamwork, communication, and cooperation. It also helps individuals to learn how to handle winning and losing in a healthy way. Furthermore, it can promote a sense of well-being, self-esteem, and physical fitness. Additionally, playful competition can foster a sense of community and belonging, which is crucial for human survival. It can also help individuals to develop a sense of perspective and to appreciate the importance of balance in life.

Caring for winning in competitive frameworks, and caring for each other in cooperative frameworks arguably give rise to varying degrees of war, conflict and destructiveness. We can generally think of a cooperative tendency as having moral value. However, if a person is cooperative only within a group, and the group itself competes destructively with other groups, we can think of the group as immoral. Immorality then dribbles down to the group members. So for us to be moral, we need to be in righteous groups that are in cooperative dynamics with other groups. This might become more apparent with a more extensive scope of care for other beings. The scope of care can be disentangled into cultural and biological concerns. People who care only about people in their own country have a lower cultural concern than those who care about people in other countries. Similarly, people who care only about other humans have a lower biological concern than those who care about different animals. The most extensive scope of care we can have is arguably for everything in the universe.